Leutnant Günter Martens |

The following is rewritten from an article orignally appearing in DIE FEUERWEHR (newsletter of GD re-enactment group) Jan-Feb 1994 issue

On 28 January 1994, I had the pleasure of talking to Gary Martens, a resident of Calgary, Alberta, who had served with Panzergrenadier Lehr Regiment 901 during the Second World War. Panzergrenadier Lehr Division was a conglomeration of several demonstration units and soldiers with experience in other field units.

Gary was originally named Günter, but changed his name when he came to Canada because people in this country always pronounced it "Gunter" which in German means "male goose." He had been a sailor before the Second World War, working on passenger liners on which the Kraft durch Freude (Strength through Joy) organization sent workers on holidays to South America. (KdF also used airships (zeppelins) for the same purpose, and it may be noted that the Volkswagen automobile was originally called the KdF Car.)

At any rate, Gary returned to Germany to do his time with the Reich Arbeits Dients (RAD - German Labour Service) which was required of all German males. Afterwards, he joined the German Army. His infantry training unit was part of the force that marched into the Sudetenland (Czechoslovakia), and later he belonged to a Schützen unit, the forerunners of the Panzergrenadiers. His Schützen unit was the only one in Poland to be equipped with SPW (Schützenpanzerwagens - armoured personnel carriers, typically Sd Kfz 251 halftracks).

Gary fought in the French campaign in 1940, and described it as a holiday. There was one instance in which his unit came upon a French barracks; soldiers there were doing exercises on the parade square, and as the Germans surrounded the installation with tanks, the French waved at them enthusiastically thinking them to be their English allies. The Germans dismounted once the area was surrounded and sealed off; the shocked French could only ask "Germans? Here already?" Gary remembered that the French were disarmed and then sent home instead of being taken prisoner.

Gary earned the Infantry Assault Badge, Wounds Badge, Iron Cross Second Class, and Iron Cross First Class in Russia, in addition to the Winterslacht im Osten (Winter War) Medal.

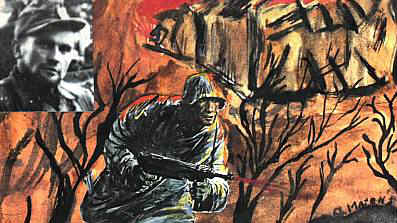

The illustration below shows an action near Ivannowskoje which occurred in December 1941; the drawing was done in 1993, the photo taken in Normandy in 1944.

The action which the illustration depicts took place at night; Gary and several of his comrades were trapped behind enemy lines and his friend came up with the idea of setting a barn on fire, so that the Russians wouldn't be able to see them running towards safety. The plan worked, though the small band felt some alarm afterwards when a large force loomed on the horizon. The men turned out to be Germans, and when Gary was ordered by their commander to accompany the force back into the village they had just fled, to locate Russian positions there, Gary admits it was the only time he refused an order during the war. Gary lost many friends there, and his regiment had been reduced to a fraction of its strength. In a strange quirk, the commander that Gary met was accompanied by a soldier who after the war would become Gary's brother-in-law, though at that time Gary had yet to meet his future wife.

Gary cast some light on how Russian civilians were treated. Despite what some have written after the war, Gary remembered that anyone who mistreated the civilians in Russia was subject to military discipline. Rape was punishable by death, though Russian girls were "so filthy" that no one was likely to perpetrate such a crime. During the winter, German soldiers were forced to live in Russian houses, but rather than dislocate the inhabitants, German soldiers in Gary's unit shared the houses with their Russian residents, even sharing their rations with the Russians. Gary asked me "How could you sit and eat, with a little Russian child sitting in front of you starving?" When the Germans arrived in Russia, many felt they were being liberated from Stalin, and the first thing many did was to put religious artifacts back up in their homes and begin to worship again. German soldiers sometimes worshipped with them.

By 1944, Gary was an Oberfeldwebel in the Sixth Company, Panzergrenadier Lehr Regiment 901. The Panzer Lehr Regiment fought in Normandy, and Gary insists that if properly supported, the Allied could have been thrown into the sea. Several armoured units had been transferred to the south of France, according to Gary, and jet fighters located in Normandy had been destroyed by saboteurs. He also describes receiving a shipment of winter clothes bound for Russia during his summer in Normandy.

Another incident Gary recalled was an instance in which a Canadian lieutenant entered a house from one direction, and Gary from another. Both men had automatic pistols, and faced each other down from a distance of a few metres from each other. Finally, Gary shrugged his shoulders, the Canadian did the same, and both men backed out the way they had come.

At the end of the war, Gary was given his final marching orders (which he kept as a souvenir). He was to take four officers with him to the front; he instead sent the four boys (who were still in their teens) home instead, and travelled to the south of Germany. When the war ended, he hid out in the hills with other Germans, afraid of the Allied prisoners who had recently been freed and were, according to Gary, running amok and looting. The Americans finally caught up with them, and told them they could keep their pistol sidearms if they wore a white armband. They agreed, and came down out of the hills to a labour camp, then were shipped off to the border with the Russians and according to Gary trained for three weeks with the US Army, in preparation for a war with the Soviets.

The training camp was disbanded after three weeks (Gary intimates that the camp was run inside American General Patton's area of administration, and that higher headquarters found out about the camp). Gary and one other officer, with one of the secretaries he met at the camp he worked at (whom he eventually married) were given a war-weary Kübelwagen with mismatched tires and allowed to drive home to Hamburg - making Gary one of few Germans to own his own automobile in post-war Germany.

Since the war, Gary has worked in Canada for 40 years, and lays claim to more Canadian patents than anyone in the world.

I had met Gary when I published a letter in the Calgary Herald to chastise that the phrase "Nazi Army" was being used incorrectly to refer to the German Army. Gary phoned me to thank me, several months after the letter was published, and after a telephone conversation I was invited to Gary's house to view his memorabilia. He still had his decorations, his Soldbuch (a replacement for his original, which was lost fording a stream in Russia), his pink-piped shoulder straps (which were prized far more than the later grass-green ones which became official replacements for the pink in 1943), and a well maintained photo album. When pressed, he rated the Polish soldiers he fought in 1939 as the best; the Canadians did not rate highly in his opinion. Gary also described large Russian stockpiles of equipment inside the Russian frontier just after the invasion in July 1941, indicating to him that Russia was planning to attack.

While many of Gary's comments may seem suspect, as perhaps apologist, there is no doubt that Gary had been a brave soldier who saw a great deal of stress and suffering while fighting for his country. He was obviously very proud of his service, and that of his comrades.