| The following information is

presented as a general guide for re-enactors and Living Historians portraying German

soldiers of the 20th Century. The German soldier was subject to multiple intrusions

into his personal life, as well as several sets of orders and regulations.

While some practices may have been relaxed in the field, it behooves re-enactors in the

public eye to hold themselves to higher standards than may have been exhibited by those

they seek to portray. The

following are based on official regulations as well as informal common practice.

APPEARANCE

Male Haircuts

Several hairstyles were popular in the 20th Century, though

soldiers in uniform found themselves restricted to what they were permitted to do with

their hair. In all cases, hair was kept short, the basic standard being that it had

to be kept off the collar and off the ears. In general, extremely short hair styles,

as found favour in the 1980s and 1990s in modern militaries, the were not common during

the Second World War.

The following information from The Haircut Site gives some examples of what

would be considered acceptable or not. (Photos also reproduced from The Haircut

Site). As well, re-enactors should keep their hair a natural hue. Sideburns

are not mentioned, but should net extend past halfway down the earlobe; even better is to

have them cut in line with the top of the ear.

|

According to The Haircut Site, the "Businessman's

Cut" is "cut long enough to be either parted or brushed back. The back and sides

may be tapered or slightly longer, and the hair is usually cut above the ears. This cut is

short, but not too short. It's suitable for even the most conservative occupations, and

versatile enough to wear differently in different circumstances." This style is acceptable for re-enactment, and will not make a re-enactor

stand out when he returns to his civilian life at the end of a weekend event. |

|

The Haircut Site defines the "Taper Cut" as

"the style of having the hair cut progressively shorter lower down towards the nape

of the head. This is generally done with electric clippers and gives a crisper, freshly

cut look. The degree of tapering can range from a slight taper to a style in which the

hair around the nape and around the ears is shaven." At left is Casper Van Dien

as he appeared in the movie "Starship Troopers."

| Re-enactors should remember to tell their barber to taper

their hair rather than "block" it. "Block" cuts have become

popular among civilians in recent years, but are still not permissible in the Canadian or

American military. The hair is cut straight across at the bottom instead of being

"tapered". |

|

|

|

White Sidewalls, or White Walls, according to The Haircut

Site, refer to "the back and sides of the head when they are buzzed extremely close

to the skin, or shaved clean using lather and a razor. The newly-exposed sides of the head

are often less tan then the rest of the face, and look white (like the white on white

sidewall tires) in comparison." The photo at left is of Ryan Tripp. A

complement to this would be a "soldier's tan", also known as a "farmer's

tan" - being tanned on face and arms, but pale on shoulders, chest and back,

indicating someone spending a long time out of doors with a shirt on. |

|

Finally, a "buzzcut" is, according to The Haircut

Site, a "generic name used for a variety of short clipper cuts, usually uniform in

length, where the hair conforms to the shape of the head (as opposed to a flattop). The

name comes from the sound of the electric clippers used for the cuts. A buzzcut

typically ranges from 1/2 of an inch to stubble (no guard on the clippers). Variations

include BUTCH - A Buzzcut where the hair is cut to a uniform, short length (usually 1/8

inch or less) all over. A butch would usually be considered shorter than a crewcut, and

the butch is even all over while the crewcut has a little extra length at the front of the

head. CREWCUT - A Buzzcut where the hair is clipper-cut short on the back and

sides, and to an inch or less on top." Matt Damon wore a crewcut in the movie

"Saving Private Ryan." |

|

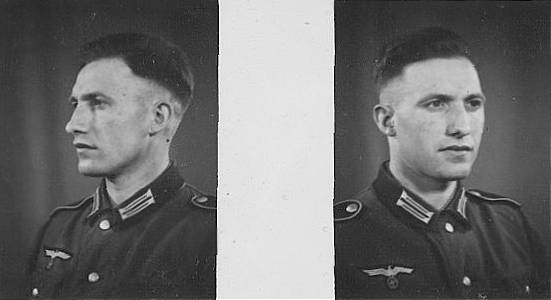

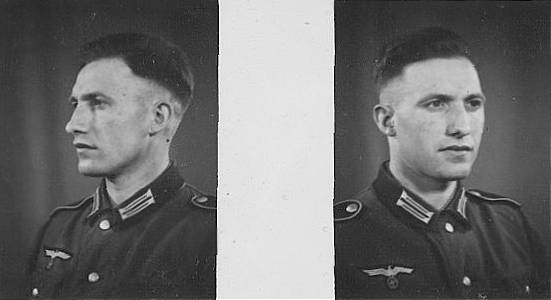

German haircuts during the Second World War varied from man

to man, but in general, extremely short styles were not seen (though some veterans of the

"Old Army" may have worn brushcuts). Hair tended to be cut very short on

the side (as illustrated by the White Walls cut above), but was left longer on top, often

treated with hair tonic. Commercial hair tonics like Brylcreem are still available

today.

A good source of information regarding German haircuts of

the Second World War is the film STALINGRAD which was released in 1993. The haircuts

of the principal actors capture very well some of the different styles seen in period

photos.

At left, German soldiers receive haircuts in the field. At right,

Obergefreiter Georg Ebner, photographed before his death in June 1945. |

|

|

|

Even senior officers got their hair cut;

Knight's Cross holder Oberstleutnant Alfred Haase is shown at right, below - note hair

shorn almost to the skin around the ears. Haase was Commander of Pioneer Lehr

Battalion 2, and was awarded the Knights Cross by Hitler on April 1, 1942. Below

left, it can be seen that hair on top sometimes got extremely long - but always kept off

the ears and collar.

Facial Hair

Mustaches were generally not permitted in the German Army. Those that did wear

them did not let them extend past the corners of the mouth. Beards were forbidden by

regulation, except by Mountain Troops, or for medical reasons that prevented a soldier

from shaving. Even in these cases, regulations stated that beards could not exceed 2

cm in length. |

|

Piercings/Tattoos

Pierced ears were not adopted by men, generally speaking,

until the 1960s as the earliest, and did not gain widespread popularity until the

1980s. Men have always been prohibited from wearing earrings when in military

uniform. Other piercings, whether male or female, are a very recent fashion trend

and was unheard of in the 1940s or earlier.

Tattoos have gained popularity among soldiers throughout the

century. By and large, however, tattoos in the Second World War remained modest in

size and crude in design. A wide variety of other designs, non-military in nature,

could also be found. Re-enactors should cover up non-period looking tattoos with the

appropriate garments. Tattoos were usualy relegated to the arms, legs, or back by

soldiers in the first half of the 20th Century.

Tattoos and piercings did not become fashionable for women

until well after the Second World War. Piercings were generally limited to the

earlobes, one per ear on the bottom of the lobe. Earrings were to be plain metal

studs.

Eyeglasses

Eyeglasses are not commonly seen in period photos, especially

not in combat units. For those who must wear eyeglasses, acceptable styles are

limited to round wire frames, or alternately, rimless glasses.

Timepieces

Wristwatches began to be common in the first years of the

20th Century; First World War soldiers were more likely to have a pocket watch,

however. By the Second World War, wristwatches were becoming universal. Bands

were in leather or metal "twist-o-flex" and the dial was a simple one with

either Roman or Arabic numerals. Day/date features did not yet exist. Non

period watches should not be worn.

Jewellery

Wedding bands may be worn on the right hand by married

persons (this is the opposite of North American practice); otherwise it is best not to

wear jewellery with re-enactment uniform. Military regulation forbids the wearing of

any other jewellery.

Decorations

Decorations for bravery should never be worn by

re-enactors. Post-war decorations, including decorations actually earned by the

re-enactor wearing the uniform, should not be mixed with wartime attire.

Exotic Kit

Seek to portray the rule, rather than the exception.

Document your sources when you adopt a uniform, insignia or piece of equipment. One

photo of one man "somewhere in Normandy" from an unspecified unit wearing a rare

piece of equipment is generally not sufficient grounds for a re-enactor to adopt the wear

of the same piece of gear. Be specific in your research.

Don't be a "Farb"

The term "farb" has gained universal use in the

re-enactor community. It is short for "far be it from me", the usual

prologue to a detailed criticism of another re-enactor's appearance. It is now a

noun meaning "poorly turned out re-enactor" not in terms of dress and

deportment, but in historical accuracy and authenticity. Allowances are made in all

re-enactment societies and organizations. Nonetheless, the acceptable standard of

uniforms has raised considerably since the 1970s. While German re-enactors could

once get away with poorly made Swedish conversions, the standard in most groups now is

custom made reproductions. All re-enactors should strive to be as authentic as

possible in terms of uniforms and equipment, while at the same time striving to

preserve and keep safe from harm high quality, irreplaceable original items.

DEPORTMENT

While away from the field, soldiers were obligated to present

themselves as disciplined and well organized, to their superiors and to the public at

large. Soldiers were ordered (and re-enactors should seek) to follow these

guidelines of deportment:

- Outer garments such as greatcoats are either worn completely

buttoned up, or else taken off entirely.

- Hands will be kept out of pockets.

- Gum will not be chewed while in uniform.

- Headdress will be taken off when in a mess or eating

establishment, or for a church service. It will be worn at all other times,

including when driving a vehicle.

- Soldiers will not lean against walls but will instead either

sit in an appropriate place or stand erect.

- Uniforms will be kept clean and pressed; shoes and brass will

be brought to a high shine with the use of polish.

- Re-enactment uniforms should not be mixed with civilian

attire.

- Uniformed re-enactors should wear their uniforms at events,

and when in transit to/from those events ONLY. Re-enactment uniforms are not

appropriate attire for taverns or restaurants.

- Commissioned officers, whether in period uniform, or currently

serving in the Armed Forces, are to be saluted with a salute appropriate to the uniform

being worn.

- All NCOs and officers superior in rank, be they re-enactors or

currently serving members of the Armed Forces, will be addressed to either by their rank,

or (for sergeants-major and officers) as "Sir" or "Ma'am."

Public officials will be addressed by the proper form or address as well (ie "Your

Worship" for a Mayor, "Your Honour" for a Lieutenant-Governor of a

Province, "Your Highness" for a member of the Royal Family, or "Your

Majesty" for the reigning Monarch.)

- Members of foreign armed forces (whether re-enacted or

currently serving) will also be paid compliments as outlined above.

- When addressing a superior, it is customary for a soldier to

stand properly at attention

How to Talk to the Public

The main goal of re-enacting is educating people about

military history. Some tips on interacting successfully with the public at large

(including veterans):

- Thank people who pay compliments on your display or your

appearance.

- Don't argue with people who say that you have done something

wrong, even if they are incorrect.

- Don't use profanity.

- When talking to veterans, don't ask awkward questions; it is

best to stay away from the question of killing people altogether. Do not expect a

veteran to be overly interested in you until you have shown an interest in him; ask him

when he joined the Army, how long he served, what unit he was in, and questions of that

nature. Sometimes they will open up, some will not want to talk much at all.

Respect whatever decision they make in that regard. Above all, listen

to what they are saying. Do not argue with veterans, even if they appear to be wrong

about something. Be sure and thank them for their service; they will not have heard

it enough, even if they do act humble and tell you "it was only a job."

- Admit when you don't know the answer to a question. Do

NOT make something up; it may well come back to damage your credibility. Some people

enjoy asking obscure or trick questions to re-enactors out of a sense of superiority or

mischief. Admitting that you do not know everything there is to know only adds to

your professionalism. Your research may also be aided by having people tell you

things you don't know already. Be open to this.

- In general, be polite, be receptive, and remember that a

re-enactor's job is to convey his knowledge to the public, as well as be an ambassador for

the unit he is portraying.

SOME PRACTICAL

RE-ENACTING TIPS

(This article by LTC Lou Brown is reprinted from Vol. 4 Issue 4 of "Der Zug",

the newsletter of a Grossdeutschland re-enactment unit in the Eastern United States.)

Most reenactors are civilians who have never

served in the military. For that reason, there are some fundamental things, common

to almost all militaries, to which they have never been introduced. Indeed, one of

the largest tasks faced in "basic training" is to take civilian habits out of

the potential soldier. (As society becomes more "free", this becomes even

harder because the norms of the military and what is usual in society tend to become even

farther apart.) One of those things constantly reinforced in basic military

training is the proper wear of the uniform and personal appearance. Good units care

how they look and exercise considerable effort to ensure that their personnel meet

established standards. They take especial pride in ensuring the "little

things" are also looked after. One of the measures of a good unit is how its

soldiers look, especially whey they are not under close

supervision. What follows are some practical tips, adopted from my own military

experience and combined with (actual WW II) uniform practices, which will help

(re-enactors) better project the image of a solid, well-trained, and motivated unit.

(Webmasters note -

while exceptions to all of these can be seen (as illustrated by the accompanying wartime

period photos), remember that re-enactors seek to portray the rule - not the exceptions.)

Headgear is always worn outdoors.

One of the hardest things to teach a recruit is remembering to put on his cap when going

outdoors. When you leave the billets or your tent at a reenactment, be sure you

have the proper headgear, that it is properly worn, and that it is removed indoors (except

when "under arms" -- soldiers on official business who are armed do not uncover

upon entering a building.)

Items are worn, never carried.

If worn, they are worn properly.

|

Soldiers don't carry overcoats, raincoats, etc., over their

arm -- the item is either worn or left behind (except, of course, as part of the field

equipment). All items are worn properly -- all buttons are buttoned, snaps done,

etc. Nothing is less military looking than someone walking around with his blouse

unbuttoned, or the cuff slits "flapping about" because he failed to ensure they

were buttoned. While many might think that such things are macho-looking, good

soldiers detest casual sloppiness; buttons are meant to be buttoned, and when they are

not, it offends the good soldier's sense of "natural order." (While highly decorated, this German

officer thinks nothing of posing for a photo with a greatcoat draped over his arm;

generally not considered appropriate, the man was probably proud of his medals (or else

the photogapher wanted a better view of them). One must always treat period photos

with suspicion; the intent of the subject and the photographer can only be guessed at,

decades after the fact.) |

Complete uniforms are always

worn. This is the corollary to the above, not the same thing.

Everything can be worn correctly, and the uniform still not be complete. While most

re-enactors get the field uniform correct, few get the German soldiers' other forms of

dress right. Off duty, low shoes and the Schirmmütze were often worn, but only in

relatively secure areas -- otherwise, the duty uniform was worn -- but this would be

entirely appropriate for wear in the cantonment area during non-battle times at

reenactments.

Soldiers generally shave once a day.

Good soldiers do not appear unshaven. Units ensure that soldiers maintain

cleanliness at all times as a matter of preserving health; part of that routine is a daily

shave. While no one would have expected the soldier to shave while bullets were

flying, part of the "after operations" cleanup would have been a return to

normal standards. Again, while some folks would find the gruff, unshaven look

"manly," a good unit would find it unacceptable.

There is no excuse for sloppiness.

|

There is a clear difference between shoddy appearance

(brought on by aging, repaired uniforms and equipment) and sloppy appearance, which is

generally the result of neglect or lack of concern. Boots are at least blackened if

polishing is not possible, belts are worn straight (not "John Wayne" style,

drooping down over the hip), blankets are not draped around the shoulder as capes, and

uniforms and equipment are maintained as best the soldier can with what is available to

him -- missing buttons are replaced, tears carefully sewn up, etc. (Note: most

repairs....on actual....uniforms are very well done, either by being carefully hand

stitched or machine sewn. Supply personnel had sewing machines available to them

(and persons with some tailor training were generally available to conduct unit-level

repairs). Additionally, severely damaged uniforms, etc, were usually exchanged for

serviceable items -- the damaged items were then evacuated to a level where, if repair was

feasible, it was done by those who knew how to do it and the item returned to the supply

system for reissue. Generally, modern armies frown on the soldier sewing up large

tears himself -- it usually looks like hell, and, worse, doesn't hold, resulting in the

loss of the item when proper maintenance would have prevented the loss. (At left, a stuido photo of a

soldier with a pen clip clearly visible under his pocket flap - generally considered a

no-no; pens, watch chains, combs, etc., were supposed to be hidden when in uniform) |

In conclusion, there is no real

soldier in the world who hasn't been dirty, unshaven, and looked like hell at some point

-- this is not, however, the natural state. Units who allow their soldiers to go on

that way don't exist for long. Good appearance and maintenance of equipment are

habits which branch into other things -- generally, they are indicators of

discipline. Soldiers who are cavalier about correctly wearing the uniform usually

exhibit the same sort of cavalier attitude regarding the really important aspects of

soldiering -- weapons maintenance, field skills, etc. Good units are built on the

sort of discipline that results when soldiers can be trusted to do what they are supposed

to without direct supervision. Real or reenactment, you can tell a

lot about a unit when you see one of its soldiers walking down the street alone; does he

look as good as when in formation, or is he out of control? While not always true,

the old adage "if it looks good, it probably is" is at least a start point for a

better-than-average unit.

Remember, you are wearing your name on your

sleeve. |